Ride On

There were many bitterly cold mornings when I pulled myself out of bed to follow the Dark as he led us through successive winters of the blanket protest. It seemed depressingly appropriate that as I rose from my sleep to fall in behind him for the last time, the morning of his funeral should also be freezing. Later in the day as he led the way through the streets of the Lower Falls shouldered by his pallbearers, the cold had abated. It wouldn’t be the wee Dark if he failed to bring some warmth to those around him and thaw the chill of inclement surroundings.

Memories of an old blanket protest ditty pushed its way through as his cortege wound its way from street to street: ‘we’ll follow the old man wherever he wants to go.’ He was a young man when he assumed the leadership of the Blanket men. But he was 29 and we were still in our teens or barely out of them. Two nights earlier outside his sister’s home where he had been waked I sang it to Micky Fitz who immediately traced its origins for me.

I attended the funeral with my wife and our two children. My son, who last year accompanied me to the very H-Block cell where I began my years of blanket protest and also traversed the wings that Brendan had presided over as IRA protest leader, was too young to understand. His older sister was told she was at the funeral of a great man. It was with a deep sense of pride that I learned from her that upon her return to school she told friends about the great man she had followed through the Falls. He knew her, and on the Friday she was born seven years ago had celebrated her arrival in his favourite local with me and the South Belfast republican, Tommy McReynolds.

Ironically the crowds at Brendan’s funeral denied him the one thing in life he craved more than anything - solitude. He had been denied it everywhere he went and was no stranger to the Sartrean concept that hell is other people. In pubs he was pestered by punters, for the most part meaning no harm but nevertheless depriving him of the much needed time he wanted to be on his own. One evening in Southampton we arrived in a bar shortly after a long road trip from Manchester. We were out there lending our support to the families and friends of political prisoners on hunger strike in Turkey. We were tired and in need of relaxation. The first pint had barely started its descent when someone who knew ‘Darky’ spotted him and latched onto him for the rest of the evening. I was fuming whereas he merely took it in his stride, saying that people needed to be listened to. We had listened to people all day and were exhausted but Brendan had a certain stamina that left me behind.

For that reason he would have been unconcerned had he known in advance that there would be crowds at his home and in his cortege seeking out his company for one final time. It would be the last journey through the streets of his beloved Lower Whack that so many of his closest friends would ever make with him. He would never have denied them that.

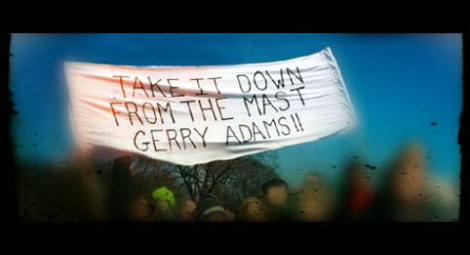

The mourners made up a mosaic that defied easy definition. It ranged from left to right of the political spectrum. Non aligned republicans, socialist activists from Dublin, the IRSP, former prisoners, Republican Sinn Fein, the 32 County Sovereignty Movement, Sinn Fein, all attended. People travelled from abroad just to be there and to stand alongside local people who had fond memories of The Dark as a guerrilla leader with the common touch. Many shouldered the coffin: hunger strikers Marian and Dolours Price, former blanket protest comrades of the Dark like Martin Livingstone and Joe Watson, men who were with Brendan on the 1980 hunger strike -Tommy McKearney and Raymond McCartney, Fra McCann of Sinn Fein – a former D Company volunteer and blanket man, Jimmy McCauley, one of the famed fighting ‘dogs’, big Fra McCullough, another D Company veteran who The Dark adored and endlessly talked about in prison. Jail O/Cs who stepped into Brendan’s shoes such as Seanna Walsh and Brendan McFarlane mingled with the men they had led.

People of different persuasions embraced each other. There was the inevitable ostracism but those doing it are fewer in number while the ostracised hardly notice, there now being so many of them.

Mass said, the oration at the Falls Road Commemorative Garden over, we made the afternoon journey from West Belfast deep into the East of the city. It was a route I had travelled with Brendan before. When my father was cremated he had accompanied me to Roselawn. Thoughts of that day drifted through my mind as I sat in the same room, Brendan’s remains now in front of us. This time I would make the journey back to West Belfast without him. In the pew I sat beside my daughter as she cried. I advised her not to move her eyes from the coffin as it would descend from view very quickly. The words of the Christy Moore song Ride On faded as The Dark was lowered to the sobs of his heartbroken family. This incorruptible comrade and resolute friend had left us for the last time.

Ride on Brendan.