Engaging with Dissident Republicanism

by Damian O'Loan

I: The Imperative of Understanding

Against the background of a concerted disagreement over dialogue with dissident Irish Republicans, one question has been asked time and again: what could these barbarians possibly have to say that is worth listening to? What is the point?

One suggested answer is that no conflict has been resolved by a security response alone. This is manifestly false, but that doesn’t make pure repression correct.

Another is that what ‘worked’ with Sinn Féin and the Provisional movement will inevitably work again, particularly given the relatively low levels of support enjoyed by the dissident movement. This may be true, but it doesn’t in and of itself justify dialogue.

Understanding dissident Irish Republicanism is important for anyone with a stake in the future of the peace obtained through the Good Friday Agreement (GFA) and associated events. That could mean anywhere from Belfast to Basra. It is essential for those who consider politics the only solution to conflict; for those who consider armed revolt the only answer to imperial oppression.

My personal motives are to better understand my own thinking, in the hope of correction where mistaken.

Firstly, what are these groups and individuals dissenting from? I will take it to be the GFA and/or a solely political approach to reunifying Ireland through the institutions created thereby.

Secondly, why are they dissenting and what motivates their action? For the purposes of this analysis, only the rationale behind the differing strands of dissention will be examined. What motivates any human action goes beyond reason alone into the more opaque waters of emotion and psychology. But let’s begin with the arguments proposed.

II: The Political Identities of Dissident Irish Republicanism

In a recent discussion, some of those who oppose the settlement approved by referendum were kind enough to share their objections and their objectives. Others are more reticent, perhaps through disinterest, perhaps due to a wish to keep their hand hidden for any future or ongoing negotiations.

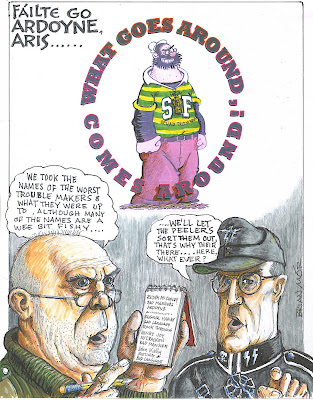

Through this and other research, some common themes emerged. Alongside devotion to Pearse, a thread of Connolly-inspired socialism, or what would now be called communism, lies at the heart of most of the strands. This is more and less informed. Eirígí supports Vietnamese communism, seemingly unaware of that nation’s joint military exercises with its avowed imperial enemy, the USA, and the latter’s supply of nuclear weapons technology to the ‘ally’. The RNU, represented by the very sincere Ard Eoin Republican, seeks a 32-County Democratic Socialist Republic, but confesses not to have developed its position greatly in its young life.

Eirígí has existed for just over four years. It is registered at Leinster House as a political party, though it doesn’t recognise the legitimacy of that institution. Its position on armed struggle is not clear. It offers no support openly, while celebrating the tradition and not respecting anything to distinguish the current dispensation from the contexts of previous campaigns.

Its position and campaign against the use of Section 44, found to be in contradiction with European human rights standards legislated for in the UK and Ireland, subsequently dropped in Britain but maintained in Northern Ireland, shames some of the parties in Stormont and exposes their occasional ambivalence towards the concept. Whether the “various other powers that can be used” mentioned by Tessa Jowell will also be challenged by the group remains to be seen.

The group has no real policy to speak of, but outlines its rejection of that dispensation and has reached a position on participation in elections. This rejects Westminster and Stormont, but accepts local government elections in the North, all elections in the South as well as EU elections. It does not overstate its chances. But is this position consistent?

Firstly, the compromise on local government elections in the North can only be explained by prospects of success, despite the STV system at Stormont. All these elections operate under the principle of British sovereignty over the affairs of the North. The local government boundaries end at the border. Any disputes are heard under the British judicial system.

Similarly, if one accepts one side of the border, one has to accept the other. The contradiction between accepting seats in the Dáil, while rejecting those in Stormont, is only justifiable in light of a need for visibility and to be taken seriously as a potential government. It amounts to an undeniable compromise, albeit one painstakingly reached.

Any EU participation would be used to create an alternative to SI, a movement as prone to schism as the Irish left and now virtually ineffective. How an alternative based on principles not a single force in European politics is prepared to defend would be structured and would attract support is not elucidated. Why cooperation with, for example, the Parti Socialiste’s ambition - to reform SI into a potent force in the face of global corporatism - is not acceptable remains unanswered, though one can infer a position too far to the left to compromise. If Eirígí has counterparts in other countries in some regards, none have the support to take a seat among the 632 offered by Strasbourg. The EU recognises Northern Ireland.

The 32 County Sovereignty Movement offers more complex presentation of an argument based on similar principles. At the heart of its ideology are two: nothing can justify partition of Ireland; that the solution is not harmonization, but addressing what it judges to be the conflict’s root cause. Rejection of British involvement on the island of Ireland is the nexus dictating every other 32CSM policy. Is it a more sophisticated ideology than simply ‘Brits Out’?

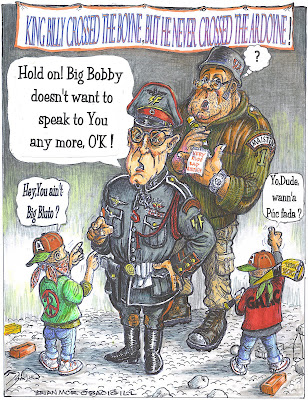

Yes. It takes that refrain to conclusions of differing logical consistency. Its policy platform is not well developed, but takes a consistent starting point of complete British withdrawal. It sees justification for this not only in the familiar uncritical historical obsession, but more interestingly in the British approach to the GFA negotiations which “pre-presumed”, or assumed, a British presence. It has, unsuccessfully, challenged the legality of British presence through the UN, a body it also suggests as capable of providing an international policing service to replace the PSNI.

This trust in the UN is not naïve; there is an increasing number of countries that oppose Britain and, regardless of the merits of the case, would seek to undermine its credibility. Yet it offers an inherent contradiction, which is acceptance of any international voice regarding Ireland’s internal affairs as long as it agrees with the basic rejection of partition. The UN, based on the compromise of diplomacy, is a singularly unsuitable medium for the 32CSM to progress its politics. What is, perhaps, naïve is the belief that the UN acts to oppose the march of globalisation, to which the movement states blanket opposition. You can see this in these two maps.

The strength of the 32CSM is its assessment of the contradictions of others. The sovereignty and neutrality that were at once professed by Westminster are ridiculed; Sinn Féin’s position that MI5 is not involved in policing; Ulster nationalism and unionism; the inherent moral contradiction of colonialisation. Taken in turn, if there ever was neutrality – which the movement appears to tacitly accept as preferable - its only vestige is the possibility of self-determination offered by the GFA. In rejecting it in favour of the rule of force and a dubious and impotent legal argument, it adopts a weaker, in terms of its favoured realpolitik, and less legitimate position than those precious few who recognise the GFA referenda and use it to their advantage.

Sinn Féin’s position on MI5 is indeed absurd, reinforced by its refusal to demand effective oversight. Its only virtue is perhaps greater clarity than the SDLP’s. Whether support for that organisation’s oversight by Stormont or others is likely to increase in the face of ambivalence regarding anti-GFA violence is less clear, or highly doubtful. Attempts to justify even torture in the name of the fight against terrorism have been disappointingly successful. A surprising number of people are willing to sanction anything in the face of a risk to prosperity. The modus operandi of the 32CSM is what justifies ineffective diversion of public money towards the military-industrial lobby and the unconstrained presence of MI5 in the eyes of those who accept it and those who don’t.

The error in its perception of moral hypocrisy regarding colonialism will be examined later, but for now it is perhaps revealing to note that the global vision of the 32CSM is entirely Hobbesian and depends on the rule of force. Contradiction, it seems, is difficult to avoid when adopting a political stance.

On evacuation of the British presence, by unclear means, the movement offers a loose framework upon which to build a framework for society. The draft of potential government departments suggest a complete disconnect from the Ireland of 2010, with priority given to the distribution of wealth over its production. Its sincerity in proposing a Bill of Rights raises the same questions the concept does in the hands of Sinn Féin or the DUP: these are not people who display a concern for human rights by their actions, less so for an attentive equilibrium of conflicting rights.

Unionism would be justified in fearing the consequences of this movement’s ascendancy. Republicans who accept the legitimacy of the unionist aspiration would be equally concerned. Unionists are advised that, again due to the perceived unchangeable wrong of partition and because “the probability of change to the sovereign status of the six county region is not an idle reference”, they should prepare for unity. The loosest of frameworks is provided, but no suggestions made as to how the 32CSM would protect individual security following reunification. Attention is drawn instead to historical injustices. At best, this indicates the ‘separate but equal’ approach of Sinn Féin, but implanted in a negation of harmonisation of communities.

III: Globalisation and Economics without Dissident Republicanism

The impact of the path globalisation has followed is not examined by any of the groups – all oppose it as an evil in itself. This is an odd position for broadly socialist groups, as globalisation was central to that movement, albeit in a very different form. Regardless, capitalism is rejected in favour of two primary economic positions: Marxism and Distributionism.

There exist better critiques of Marxism than I could provide, but we can examine the difficulties with the doctrine without reference to the USSR and only to Irish republicanism. This is a totalitarian doctrine, regardless of its political face. Its unapologetic deference to the totality of the implications of history’s significance, as well as its inflexibility regarding the evolving nature of human capacity and need are intrinsic to its application. There can be no permanent revolution under a Marxist state, only elite reform; it reaches a truth paralleled by Catholicism but rejected by 21st Century democratic compromise. It is not the politics of Chavez, Lula or Morales, all of whom have adopted, whatever their rhetoric, the social democratic compromise that lay at the heart of the dispute between Camus and Sartre. Assessing again Marxism’s suitability for humanity complements an assessment of Yeats as a symbol of Irish republicanism.

Distributionism differs in the status conferred to the state, which should be small. It is the economics of Catholicism, the BNP and NF. It is an economic system reminiscent of the democratic political system discovered by

Adopting such totalitarian economic doctrines negates the possibility of dissident republicanism engaging with and contributing to the increasingly necessary debates around financial regulation and fiscal justice.

Aside from alliances with nations who may or may not wish to ally with such movements, we have little else to understand. No monetary policy outside of some rejection of the Euro and the ‘capitalist EU superstate’. No energy policy sufficiently developed to ensure its delivery. No ideas on jurisprudence. No positions on the exploitation and trade of raw materials beyond some ‘green’ adhesion.

None of the groups or individuals place Catholicism at the heart of their ideology. Their struggle is not for Rome, it is unapologetically nationalistic. It is Behan and not Benedict driving these movements.

IV: Dissenting from the Good Friday Agreement

Broadly speaking, we can distinguish various degrees of far left politics under an umbrella of rejection of the Northern Irish state as a platform for their pursuit.

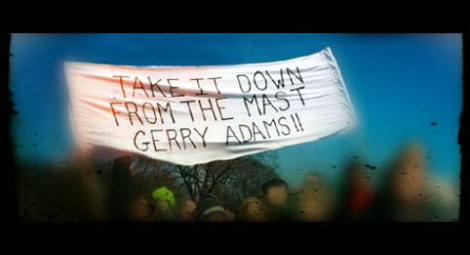

What of the justifications for that rejection? Generally, they are marked by a shared acknowledgement of a perceived or intolerable loss of sovereignty incurred by accepting the legitimacy of the Northern Irish state. One dissident pointed to Parnell’s words adorning his monument: “No one man shall have the right to fix the boundary to the march of a Nation.”

There are three degrees of refusal, which can be distinguished to some extent.

The first acknowledges that perceived loss and finds it ridiculous. You may find this position held by unionists, loyalists or dissident republicans. It states that for a nation to vote in favour of its dissolution is absurd to the point at which it needn’t be taken seriously. The contract of Good Friday could be compared to the contract of slavery viewed through this prism. Tragic, pitiful, but nevertheless absurd and thus not to be given weight.

The consequences of this differ when the eyes are those of a unionist or a dissident republican. The former can use it to justify the permanency of the union and reject the transitory nature of the GFA, allowing a sense of comfort at the price of honesty. The dissident accepting this narrative can be nihilistic, need believe in nothing and justify no conception of legitimacy of one state or the other. He or she can resign from political engagement, deny empathy with victims and successes, and dream of the bygone days when Irishmen and Irishwomen knew their origins and destiny, or get rich quick with disregard for the law.

The first is the meeting point of the nihilistic dissident and the dishonestly complacent unionist.

The second goes further and engages. It claims that there is simply no possibility of a democratic 6-county statelet founded on the basis of the ill-fated British gerrymander of 1921. That to attempt to do so is to give false legitimacy to a wrong recognized in legal systems the world over – you have no right to ownership of stolen goods. This principle of natural justice can be invoked to refute the referendum’s validity. The question, it says, should never have been asked and is only tolerated by corrupt and complicit international law. It finds a justification therein for ensuring the North becomes a “failed state”, thereby displaying its approach to the empirical approach it claims.

What are legitimate, it declares, are Pearse’s declaration in 1916, the Sinn Féin rule of 1919 and the traditions of Irish nationalist rebellion since centuries before Wolfe Tone. They are legitimate because they respect the natural order of Irish property of Ireland and sovereignty of state. The Catholic Church depicts the right to property as a consequence of divine order. Some dissidents take God to be the source of their stance’s legitimacy, and are in the company of most of the ‘martyrs’ and ‘heroes’ of generations now passed. Some take an unelaborated vision of a justice transcendent to any human decision, with no need to reference God to be Truth.

How can an Irish citizen vote to have no say in the future of a part of his livelihood while remaining faithful to Ireland? Worse, how can he or she give up a voice only to give it to a British imperial thief or their descendants? How can that be right? Democratic?

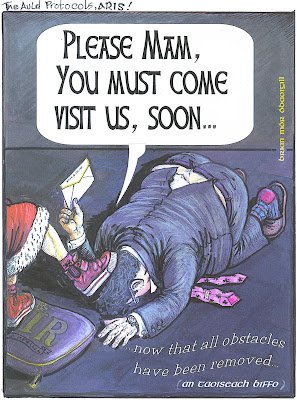

V: Answering Dissent with Respect

Herein lies the most subtle amalgam. That same dissident will vote for elected representatives in the reunified Ireland. Or, if he or she is an anarchist, will wish to appoint temporary spokespeople. Catholic Queens, philosopher kings, fascist dictators - every single political system involves giving a voice to another to represent you. Fascists say it makes them stronger; democrats say it improves their democracy. There remains only Athenian direct democracy. But it was by direct democracy that this bizarre settlement was reached and approved. Not by the English, but by the unionists and republicans who share the island. Not by the one man Parnell feared, by all Irishmen and women. To reject the result of that expression of Irish Republican will is to fall into that absurd contradiction called totalitarianism, which says you can give your voice to anything except what I predetermine to be forbidden, revolution against my “pre-presumed” order.

How this remarkable result was achieved, the manipulation and ‘acceptable’ violence, hypocrisy and lies, grooming and dismissal, can only be considered in light of the legitimacy that the referendum provides. The rewards for violence that tarnish the outcome are only challenges left by Washington, Dublin and London. No election provides the clear expression of every citizen’s short and long-term interests; it is the absolutist response of the dissident movement that is the seed of its own inevitable failure.

What makes democracy worth tending is its capacity to vote for its own degradation or growth. It need not respect the commitment to free trade and stability that made the Agreement acceptable in Washington, London & Dublin. It can vote itself free of any or all of them, just as it voted itself free of Connolly and Carson. The distinction between reserved and excepted matters, while part of the Agreement, becomes meaningless by its implication. Constructive ambiguity.

The 32CSM position on democracy is uninformed by progresses in the age of Enlightenment, even ignoring its Ancient Greek philosophical basis. It defines democracy as what happens in a sovereign 32 county Ireland, and defines as democratic any action it considers in harmony with that goal. No limit is placed on these actions. To call its adhesion to democracy superficial would be generous; it abuses the word in a manner as striking as any speech of G.W Bush, betraying the same disregard for the reasons the democratic compromise was favoured over the short-term gains offered under imperial or monarchic rule. Any comparison with the French revolution of 1789, even the Russian revolution of 1917 or the Bolivarian uprising would be wildly inappropriate. The concern is pure nationalism, not citizens’ security or self-expression.

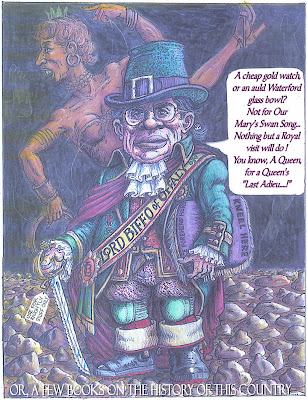

The GFA has some remarkable consequences. All the 1916 commemorations and Milltown salutes have to be considered as remembrance and nothing more. They play no part in the future, except that which survives the criticism we subject them to. Whether the deaths were worth it, could have been avoided, is a pressing matter for reflection. Not a matter of inspiration for the next generation of Irish Republicans to shoot and kill, but what came before the vote for peace. Just as British military parades should be.

The GFA is, among other things, an act of bloodless revolution by Irish Republicans who just didn’t care what happened in the North, as long as they stopped killing each other. The affirmation that a woman from Dublin who cares only about her career has a vote whose value equals that of a Provisional volunteer and a resolute Orangeman. It is not the Death of Irish Republicanism; it is its vindication and renaissance. And its renaissance accepted the legitimacy of the unionist aspiration, of two states inextricably bound.

Giving birth to a dysfunctional child whose Siamese twin was unionism, some of those who saw comrades die and who sacrificed in ways beyond my comprehension recoiled in horror. That more didn’t is a sign of the autocracy of their movement and its leaders and an indication of the fragility of peace. The dangers of a nihilistic revolution under autocratic rule were elucidated by Camus regarding the FLN and his analysis has since been tragically vindicated.

So to the third group, who feel that the only thing to do with ‘illegitimate bastard Siamese twins’ is to kill them. Their logic in justifying their actions differs little, or not at all, from those resigned to the hopelessness of armed struggle against an infinitely superior military opponent. But we can pass judgement on their actions now on the basis of the democratic laws we have, be they from Dublin, by way of Strasbourg, from Westminster or from Stormont.

None of this defends the St Andrew’s carve-up, government by segregation and appeals to its endurance, incompetence or corruption. It simply orders a path to solve problems, orders but allows that order to evolve.

Irish republicanism does need to be invigorated and updated, to question all of its assumptions. Few individuals or parties represent and lead Irish people. The limitations dissident republicans place on themselves by adopting a retrospective, introspective and undeveloped platform mean that, as with other issues, they have little contribution to make to that challenge.

For wider society, the GFA gives us obligations we have agreed to. It gives us no right to torture dissidents, to hold them without trial, to punish their thoughts. At the price of justice and recognition of the basic dignity of humanity we can do all those things. In just the same way as the Provisional IRA said anything was justified in the face of certain British crimes, there are those who say anything is justified in the face of those who don’t respect the democratic voice of the Irish people or the unionist aspiration it embraced. But if the dysfunctional child is to grow into something like a healthy adult, it will need boundaries, respect and space to dissent without harming others.