Wiki-Dump

All correspondence in relation to Allison Morris' and Ciaran Barnes' complaints and the NUJ's handling of the issue.

Dolours Price Archive

"I look forward to the freedom to lay bare my experiences unfettered by codes now redundant."

Irish Republican Movement Collection

Annoucing the Irish Republican Movement Collection online archive at IUPUI

The Belfast Project and Boston College

The Belfast Project and the Boston College Subpoena Case: The following paper was given at the Oral History Network of Ireland (OHNI) Second Annual Conference in Ennis, Co Clare on Saturday the 29th September 2012

Challenge and Change

Former hunger striker Gerard Hodgkins delivered the 2013 annual Brendan Hughes Memorial Lecture

Brendan Hughes: A Life in Themes

There is little to be gained in going from an A to Z chronological tour of the life of Brendan Hughes. The knowledge is out there. Instead a number of themes will covey to those who are interested what was the essence of the man.

55 HOURS

Day-by-day account of events of the 1981 Hunger Strike. A series in four parts:

July 5 ● July 6 ● July 7 ● July 8

The Bell and the Blanket

Journals of Irish Republican Dissent: A study of the Bell and Blanket magazines by writers Niall Carson and Paddy Hoey

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

Rafa

Rafa will always be remembered fondly by Liverpool fans for having won the Champions League in 2005. 3-0 down to AC Milan at half time with seemingly only a remote chance of getting an Everton result – a respectable defeat - I left the Belfast City centre bar where I had watched the first half with another former republican prisoner. As the door swung closed behind us I ruminated that the Italian side could run riot and inflict the worst European defeat on Liverpool in its history. The best that could be hoped for was stopping them scoring any more. I was dejected and my friend didn’t care in the slightest.

Miracles don’t happen for the very simple reason that there is no miracle maker. But it is tempting to describe as miraculous – probably because what followed next was beyond belief – events in the second pub. It was as if we had flipped worlds and were now some place totally different. By the time we had taken our seats and made ready to shift our whiskies, it was already 3-2 and Xabi Alonso was stepping up to take a penalty which he failed to convert but managed to get right on the rebound.

At the risk of making an understatement, joyfully stunned is the best way to describe the new sensation lifting my being.

The bar was closing as the game concluded at 3-3 and there was nothing left but for the players to take their penalties. An awful way to end a game, particularly one as good as this, which should have been crowned with a victory in open play. We got a taxi and listened to its radio as all or nothing faced the spot kickers from either team. I managed to get into the house just in time to watch Liverpool secure a momentous victory which took away the cloud that had hung over the club from when it lost the 1988-89 title in the final minute of the last game at home to Arsenal. It was the season when 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death at an FA Cup semi final in Sheffield. For them alone the team should have taken the title but failed lamentably.

That side under Kenny Dalglish, although a great player and manager, seemed not to have the bottle required to lift the double. For the second season in a row the League and Cup brace eluded them as they folded in the final game.

Istanbul cleaned the slate on that. However, if Rafa did the job on that splendid evening, when at half time he talked to the players, it was a one off which he never seemed capable of repeating. He benefited from the public belief that the success on the evening was down to his pep talk. It probably gave him a longer lease of life at the club than performances otherwise merited and allowed him to buy the type of players other clubs were only too glad to sell. The inspirational leadership of Steven Gerrard on the pitch, which was repeated on numerous occasions since, probably explains the side’s comeback better. But even he has gone to seed in a team that wears the Liverpool shirt as if it were a straitjacket.

There is some talk that Liverpool are considering at some point going back to the old boot room style of developing managers from within, even said to be grooming Jamie Carragher as a future coach. In the modern game that is not going to work, resembling as it does some crude form of autarky and protectionism. In 1967 a Celtic team could win the European Cup against Inter Milan with eleven players who lived within twenty miles of Glasgow. That won’t happen again. Soccer, whether we like it or not, has moved in tune with the hard world of business. Trying to recruit from within the club is a blinkered view that will overlook visionary talent from further afield. Too small a pool.

As for Rafa, there was the sense that he loved the club if not all those associated with it. It is unfortunate that he did not deliver the goods. His forays into the transfer market were dubious. He needed players, had limited funds but did he have to visit the fairgrounds of Europe in search of any old donkey no longer able to carry kids and in need of greener pastures? And yet what will prevent his portrait hogging the Hall of Shame will be that night in Istanbul, even if a lot of the glory he got was of the reflected type.

Tom Hicks and George Gillet, the current club owners, now they are names to forget, or if remembered, then only for ruining not reigning.

Monday, June 28, 2010

Sunday, June 27, 2010

Dunked Out

This morning my wife, after handing me my birthday presents from herself and the children, was winding me up. She bantered that, having read the article I wrote yesterday predicting their demise, if England won I would take a lot of stick. It didn’t bother me in the slightest. More chance of me being 21 today. I knew I would get another birthday present late in the afternoon courtesy of German soccer skills and England’s lack of them.

The pundits have at last come to their senses and are admitting what a woeful lot the England team were. We were telling that from the opening game. And for our endeavours were accused of being England haters riven with historical spites and past sleights. Up until now the pundits assumed the demeanour of a curious religious sect who believed a divinely appointed messiah from Italy had arrived who would rapture the side into World Cup nirvana. Now they are talking about sacking him. Next time we see them they should be outside some shopping mall wearing flowing gowns, jingling bells and chanting. As useless as the team they offer ‘expert analysis’ on.

The English goalkeeper David James was the best player on their woeful side despite conceding four goals. That just about sums matters up. True, they were robbed of a certain goal but no point in blaming the referee. He like most others doesn’t expect England to score goals and instinctively ruled Frank Lampard’s over the line shot out, not even pausing to give it a second thought. We will hear much of that until the next World Cup. Same as they prefer to show us Diego Maradona’s handled goal in the 1986 tournament rather than the goal which saw him finish after stupefying the English midfield and defence with some scintillating dribbling skills.

In the closing minutes of today’s game against Germany the commentator suggested the referee should blow the final whistle and put the England team out of their misery. No doubt had he been a vet he would have put them to sleep. Revenge of sorts for the audiences they have put to sleep with their less than dazzling displays of soccer.

Overall, England did much better than I expected. They managed to get out of their group and they did win a game. No easy feat for a team with clay feet. But ultimately today’s result put an end to the nonsense we have endured about their potential. It put matters in clear perspective. Up against a side that counts in terms of international soccer, they proved their true worth, and were found to be absolutely worthless. England’s biggest contribution to international soccer tournaments is not to turn up. Look at how good the last European Championships in Switzerland and Austria were when not graced by the English presence.

From Durban to Donkeyland the braying nags of English soccer are on their way home. Good Riddance.

Saturday, June 26, 2010

Fewer Donkeys – More Hay for the Horses

Well, not exactly, but that is how it will figure in the minds of some who think the invisible men of a celestial world poke into worldly affairs in response to some mumbled mumbo jumbo. Nonsense it may well be but it helps explain the scientifically inexplicable - a drove of donkeys managed to make its way through to the World Cup’s round of 16. Whatever the reason for that uncharacteristic success, few believe that England made it as a result of their soccer ability. Easier to believe in gods and miracles.

I didn’t get to watch the England game against Slovenia which saw the English scrape through. Like many others who missed the game, probably, I was busy with things I would rather not have been doing. Later in the evening I managed to watch the Germans take on Ghana, a match the Germans needed to win in order to make the knockout stage of the competition. And what a game it was. Both teams played some brilliant flowing football and the result could have gone either way. As well as wanting to view a great match I was also interested to find out who would knock England out in the next game, Ghana or Germany. An outstanding goal sealed it for the Germans.

Match commentary is an intensely focussed activity. Those good at it convey the atmosphere from the stadium to the viewer. Peter Jones of BBC Radio 2 back in the 1980s was so accomplished at match commentary that he could even convince the listener they were in fact viewing the game. Pity the poor commentator who draws the short straw to report on England games. It would go something like this:

Donkeyonkis picks up the ball and passes it over to Donkeyakis. It is now fed out wide to Donkeyopoulos who sweeps it in to Donkeyumpus. He takes it and stumbles his way into the 18 yard area where he falls over it. After much braying from the England side the referee awards a penalty which Donkeyagoulis now steps forward to take. The spectators pause in anticipation as the England midfielder swings his hoof and … hits the corner flag. Some England fans are cheering. It is the closest their team has come to scoring in 73 minutes. Donkeynagalot protests to the referee that it is the ball’s fault and is sent off for a second bookable offence – whinnying at the referee. England are in disarray as their mane player trots off to the paddock in disgrace where a brown bag is placed over his nagging head to reduce hyperventilation. But he is sniffing around the bag for a sugar lump. He has yet to learn that England players only get treats when they do something right.

In an autobiography detailing his playing career with England, Bobby Charlton boldly stated:

I fervently hope that Fabio Capello can lay down new foundations and that in ten years time we might just be able to invite the world to see first hand our love of the game – and a national team in which once again we can invest some pride.

Yet, some English football pundits on television the other night seem to have accordioned ten years into two. They insulted their viewers by proffering as serious commentary the notion that man for man the England team outshines the German side; that they would not replace one of the English first eleven with a German player. Big Heskey with a searchlight strapped to his head still couldn’t outshine the Germans. Jamie Carragher, Peter Crouch, better than the Germans – which Germans? Carragher is probably faster than Lothar Matthaeus today but it is a while since Matthaeus turned out for a German side. Crouch, with a possible future as a safari giraffe, might out jump Guido Buchwald who, at a mere 6’ 2”, is a dwarf by comparison. But Buchwald is 50.

Enough of the rubbish. Donkeys go home. Time for the steeplechasers.

Friday, June 25, 2010

Sunday, June 20, 2010

Remembering The Dark in the Cooley Mountains

Today The Pensive Quill carries an article by guest writer, blanketman Thomas 'Dixie' Elliott on the Dark's recent commemoration

As we pulled into the centre of Omeath, my wife, my son and myself, a sense of disappointment gripped me. I saw Hodgkies and one or two others sitting in the sunshine waiting and my first reaction was, I thought more would've turned up.

I needn't have worried because we were early and before long they came and gathered outside the local pub. Mackers, Big Ricky O'Rawe and of course Hodgkies himself. Others mostly with Belfast and Dublin accents soon gathered, waffling away as we waited. Mackers had brought his son and daughter, Ricky's daughter had come along and I had brought my son who is twelve. Those of us who had the honour of knowing the Dark as a leader and a comrade who inspired all who knew him, were bringing our children in the hope they too would be inspired by our memories of this small man who had the strength of a giant. How fitting that his ashes are strewn on the very mountains where the profile of Slieve Foy is said to resemble the sleeping giant, Finn MacCumhaill.

We got into our cars and a bus and in convoy made our way upwards into the Cooleys. On the way up I spotted a wooden house that should have been built in the Swiss Alps and not the mountains above Carlingford Lough. I thought who ever built it should have had the good manners to be standing outside yodelling for passing travellers.

Soon the leading cars came to a halt at a place where the only thing I could see was a very high mountain ridge towering above us with a track leading up in that direction. Jeeze I said I hope the Dark didn't get his ashes scattered away up there. Those who knew otherwise laughed and we followed them on foot up the leafy track. I would say there was about 100 of us who had made the journey and the conversation was about one person An Dorcha, I'm sure he was there somewhere listening as we passed, but I only saw curious sheep.

Just as I was beginning to believe that the old devil had indeed had his ashes scattered on top off that mountain those in front began climbing up a rickety set of steps and over a stone wall. The crumbling walls of an old cottage long ago abandoned by Dark's ancestors stood defiant against nature's advances, sheltered from the winds that swept down the Cooley mountains by ancient trees.

A small area, strangely enough the size of a prison cell, was cleared in the tall grasses that must at one time have been the garden of that crumbling cottage. Here stands a monument that was obviously built by the love of a family for a departed father. It hasn't the grandeur of those in Glasnevin nor Bodenstown but never-the-less it is a monument to a common man who doesn't need his unbreakable spirit or selfless courage engraved in granite, it is engraved in the memories of those of us fortunate enough to have known him.

The Dark's brother, his comrade from D Company, Hodgkies and a comrade from Australia stepped forward to speak and while I listened I looked out over the fields and off into the distant coast line of County Louth and the Irish Sea that faded into the haze of the sunshine. As they told us that Brendan The Dark Hughes was foremost a Socialist and then a Republican I couldn't help but think that someday thousands will gather round this crumbling cottage to be inspired by a man who shines as bright as the sun did today and whose memory will never fade in the hearts and minds of future generations.

It is places like this that will keep the fire of Republicanism burning brightly and not Stormont, Leinster House or Downing Street. I heard Dark's family say those coming each year were growing in numbers and I hope that in years to come others will follow us up that mountain road to remember on the Dark's birthday a man who gave everything for the cause and took nothing in return.

Saturday, June 19, 2010

A Boring Rip Off

As hard to listen to as it is to watch, because of the desiccating drone from the horns, South Africa will be remembered for many things but not for the brilliance of these finals. It is so boring we could be forgiven for thinking the teams were competing for the Peace Process Cup rather than the World Cup.

France have been pathetic, England Rubbish. England can’t play as a team and France can’t play; England play as if they can’t win, France as if they are afraid to win. No point in getting too purist over Thierry Henry’s handball getting France to South Africa and ensuring Ireland would watch the games rather than play in any. It was a moment of opportunistic cheating rather than planned corporate fraud. It should no more be frowned upon than a push in the back or the tug of a shirt in the penalty area. It is a universal feature of the game. Giovanni Trapattoni’s team would not have objected to having gone through on the basis of a little push or trip unseen by the referee. Yet the Irish would have played with heart and put some passion into their performance, win or lose. Those with the least expectation hanging over them play with the fervour of those unafraid to lose. North Korea’s performance against a lacklustre Brazil side underscores the point.

If Algeria were not disappointed with last night’s result they have little cause to be. They should have stuffed that dysfunctional team fielded by the English. What did Fabio Capello actually do before he came to manage England? I know that somebody by the same name coached Real Madrid to La Liga victory before Bernd Schuster took over. Must have been a lookalike. Judging by the England performance this guy was a chicken farmer in his previous job. He has pulled together the most accomplished team of chicken chokers ever witnessed wearing football shirts. And now the Italian master baits his team with frowns and exasperated expressions to which the team respond in idiotic fashion, in the belief that coming last is better than not coming at all. Better had they stayed at home. The Irish at least have an excuse for non-performance.

Although a cliché at this stage it is axiomatic that soccer at this level is a business rather than a sport. The millionaires who patrol the pitches of South Africa have the demeanour of boring Belgian businessmen and not that of athletes at the top of their game. Billions are being generated but very little sporting acumen is on display.

A rip-off.

Sunday, June 13, 2010

A Failed Explanation

I just finished reading Powell’s Great Hatred, Little Room.

I was struck by two related aspects of the book: the extent to which the British state was successful in managing republicanism, in realizing a series of agreements that included republicans but excluded republicanism, if I may borrow Anthony McIntyre’s phrase; and the continuing dominance of the Irish revisionist perspective on the northern conflict.

On the latter point, Irish revisionist understandings of the north generally emphasize four principal themes:

1. that the conflict in the north is primarily if not exclusively internal in nature;

2. that traditional nationalism and republicanism are the main causes of the conflict and they continue to have a particularly debilitating influence on northern politics;

3. that the politics and ideology of the unionist bloc have a special significance and must be accorded privileged recognition; and

4. that the British state is a neutral and salutary force whose intervention is to be welcomed and extended.

Powell’s analysis is entirely consistent with these revisionist themes. On the first point, Powell likens the northern conflict to an “incomprehensible dispute between two tribes,” which is a view the title of the book is meant to underline. His reference to the “two tribes” is not meant to suggest that both main communities in the north are equally to blame. Nationalism and republicanism are the major problems to which unionism and loyalism are reactions (see below). This internal focus, of course, absolves the British state of any responsibility for the conflict. According to Powell, the issue is not that Britain is to blame, but that both sides think that Britain is to blame. To be fair, he does admit that the British government is not “entirely blameless,” but only in the most minor and technical ways: it sometimes made well-meaning mistakes, it occasionally had to break promises, as did all the parties, and it set deadlines too often. For Powell, Britain is culpable only insofar as it ignored the north for too long. Once the British government decided to devote considerable time and attention to the north, resolution of the “Irish question” had begun.

On the second point, he suggests that Britain’s primary purpose in entering the peace process was two-fold: to end republican violence and marginalize or defeat the demand for a united Ireland. In this, the British government was completely successful. The Good Friday Agreement and subsequent agreements relegate nationalism and republicanism to simple expressions of political identities that are to be granted “parity of esteem” within the north. This relegation effectively empties those doctrines of the very elements that represent challenges to the established constitutional and social order.

On the third point, Powell offers numerous examples of how the British government gave priority to upholding the unionist veto (disguised as the principle of consent) and worked to reassure unionists that the Union would be upheld: from the triple lock’s evisceration of the Framework Documents in 1995, to Blair’s speech in May 1997 on the value of the Union, to the progressive weakening of North/South bodies during peace negotiations, to the adoption of Trimble’s idea of an Independent Monitoring Commission.

On the fourth point, Powell variously describes the British government’s role in the peace process as a “neutral intermediary,” “neutral broker,” “referee,” and “intelligent facilitator.” He does recognize that, being the sovereign power in the north, Britain affected what happened on the ground. But, he suggests, it intervened in ways that demonstrated its lack of selfish interest in the north: it built trust between the communities and promoted fair compromises that satisfied both sides.

Powell’s book, like Irish revisionism, fails as an explanation of the northern conflict and peace process. It misunderstands the respective effects of nationalism/republicanism and unionism/loyalism, and it misrepresents the partisan role of the British state in reproducing social division and political hierarchy.

But, in many ways, this book is a testimony to the triumph of Irish revisionism as a political project. The Provisionals have, in effect, accepted the principal tenets of revisionism, however much they rhetorically oppose them, and supported a peace process that frustrates the constitutional, political and social aims of republicanism.

Saturday, June 12, 2010

Tossers United

The result was a surprise as I didn’t really expect England to get anything out of the game. A draw wasn’t a bad outcome for them, more in fact than the sorry bunch deserved. They were flattered by it. A disjointed lot who seemed to think midfield was a region in the Australian outback, they left us watching the local park spectacle – boot the ball high and far and hope it finds the head of the big lad up front. How that lot could ever feign to compete with the likes of Messi suggests something of the delusional, probably the residue from a colonial past, when they actually could strut the world stage rather than stumble across it. They are a hee haw team of donkeys, more suited for fair grounds than football stadia. A few weeks back a friend told me he felt England would lift the trophy. I asked him if he felt Ireland would be united by 2016. It takes someone with an ability to look reality straight in the back side so closely that they lose their head right up it, to entertain that sort of impossibility.

Yet we know only too well that people think all kinds of strange things and they don’t even have to be religious. In 1978 in Cage 11 people could actually be found predicting Scotland to take the World Cup, staged that year in Argentina. How anybody could persuade themselves that such a thing was possible defied all logic. My forecast that Peru would stuff Scotland in the first game led to me being dismissed as hopelessly biased. A bigot I think was the term used. Some of these guys actually had pretensions to lead revolutions. One later publicly explained why he believed Freddie Scappaticci was not a British agent. Beliefs, strange things, not always the product of reason. How could England taking the World Cup be associated with reason? Chalk and cheese.

Take a look at this lot of England muppets. More chance of Iris Robinson taking the DUP Virgin of the Year award than England picking up the World Cup. If they really want success they should consider entering the World Knuckle Shuffling competition. That is something they could win easily overcoming, or coming over some might say, whatever competition took to the field. All the terminally stupid who follow them could chant ‘come on England’. And England would duly oblige.

Summary of tonight’s game: donkeys cheered on by dullards.

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Room

A political memoir is often a dry affair for the reader, but Jonathan Powell has interjected sufficient wit, vignettes and anecdotes into his that the mind does not become parched and croaked with the minutiae of detail and negotiations. An oiled mind doesn’t choke on the dryness of footnotes. There is only so much political humdrum the average reader can be expected to swallow without the aid of a lubricant.

One such moment of wit emerges when Powell reveals that at the height of the Garvaghy Road dispute both sides gathered to meet ‘at the appropriately named Nutts Corner.’ During that same dispute there was a crazy moment when the loyalist solicitor Richard Monteith accused Tony Blair of lying. Powell reached across the table to choke Monteith but apparently thought better of it. Powell was outraged that Monteith would hurl such an accusation at the Prime Minister of Britain. But if Powell was to choke everyone who said what they thought about Blair’s ratings in the honesty market he would need to be more octopus than human. Were Monteith for his part to get upset at lying politicians spoofing, he may emigrate to Mars and from there read about the political class denouncing him for having set up home on Saturn.

David Trimble, who is not renowned for his sense of humour, nevertheless has a moment, perhaps unintentional, attributed to him by Powell. The then UUP chief summed up his own dilemma wittily enough when rejecting advice to make friends in other parties; ‘why should I make friends in other parties when I have none in my own?’ Tough at the top for Davy no Mates.

What political players think of each other makes for a valuable addition to the historical record. It enables a better construction of the political map the reading public uses to guide it through incomprehensible terrain. Overlain with human interest and accounts of human foibles the map loses its dull sterility. It is no longer a flat surface guided by the straight and predictable but assumes three dimensional qualities, revealing depths, contours, crannies, nooks and crooks. Another lubricant to oil the wheels of intake.

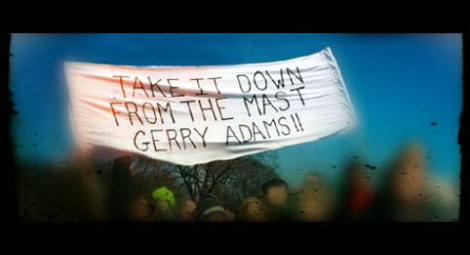

A paradoxical feature of the map Powell draws is that he keeps its dips for the Sinn Fein president. The odour of pure disdain wafts from the pages for Gerry Adams alone. It is not extended, to the same extent, to other political leaders. Paisley comes through okay. Powell may have found David Trimble ‘irritating’ but he felt history would remember him kindly.

Why he reserved his more caustic comments for the Sinn Fein boss who he felt always disappeared at moments of difficulty puzzles because it collides with a sense of something else that Powell entertains about Adams. He has publicly called Adams his friend, as well as inviting him to his wedding.

Powell in his book describes Adams as something of a bully who hectored to get his own way and behaved ‘rather sneakily.’ At one point he told the British ‘he wanted to avoid history lessons and then proceeded to give us one.’ His voice was like treacle, ‘both wheedling and threatening.’ Negotiations for him had always to be a drama. Powell noted that even Martin McGuinness mercilessly teased his boss about being a tree hugger. Nor did anyone believe that his pleas on the killing of Robert McCartney were genuine. Powell also contemptuously commented that Adams’ ‘first demand in any negotiations was normally to be fed’ and then he would complain about the quality of the dish. The memoir also likened the Sinn Fein president to a political hagfish – a creature once described by Richard Dawkins as extremely slimy. The disdain for Adams is as unmistakable as it is palpable.

Now depending on your perspective on these matters Adams could be all of these things or none of them. But the lack of symmetry between memoir and musings prompted me to raise the issue with Jonathan Powell on the one and only occasion that our paths crossed. He flatly denied holding Adams in contempt. I resisted a Monteith moment, feeling Powell was opting for diplomacy rather than dishonesty.

Later I found myself driven to reflection when reading in the memoir that Adams had challenged Powell to a TV debate, promising to wipe the floor with him. Powell must surely have licked his lips when he watched the Sinn Fein leader taken apart on RTE’s party leaders debate prior to the 2007 general election in the Republic and silently muttered ‘no contest.’

What probably made for an uncomfortable moment for Sinn Fein devotees was the Powell revelation that Adams had requested him to help draft a keynote address to the party faithful. Powell professed to being absolutely amazed when Adams ‘delivered the speech … with the draft passage contained within it pretty much unchanged, saying the IRA would disappear.’ The delivered speech was so close to what Powell wrote that the British mandarin facetiously commented on a television documentary that he did not know whether to be delighted or sue Adams for plagiarism.

Nor was this an isolated incident:

I gave them a draft of a section of a speech I had written on the future the IRA. ... It was an odd sensation to hear it coming out of Martin McGuinness’s mouth later that evening at the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis.

There are a number of errors in the book. Powell mistakenly thought Dave O’Conaill was chief of staff of the IRA in the 1974-75 period. It was a position the late IRA senior figure never held. Of greater magnitude was the erroneous dating of the IRA killing of Frank Kerr, an incident he cited as evidence that the IRA was up to no good despite its commitment to a complete cessation of armed activity. Although the killing occurred in 1994, a few months into the ceasefire, Powell placed it in 1995 at a time when there was much more evidence courtesy of the IRA’s killing campaign against drug dealers under the cover name Direct Action Against Drugs. Powell also got the date of the murder of Robert McCartney wrong by a matter of weeks.

That killing provided a window on Powell’s thinking of IRA members on the ground. Robert McCartney, he claimed, was ordered killed by a local IRA capo. This served to reinforce his view of IRA volunteers at local level as little more than thugs who drove around in four wheel drive jeeps terrorising the community. This type of activity combined with the Northern Bank robbery and other money making schemes led Powell to conclude that it should be a British objective to get the IRA onto the right path and prevent it degenerating into a mafia. Most would imagine that this should have been the task of the Sinn Fen leadership and not the British.

Yet on the grounds of expediency Powell admits to turning a blind eye to IRA activity including those aspects he viewed as unalloyed criminality. This underlines the extent of British collusion in undermining their own laws. And it makes a mockery of British claims today that the law should prevail. Clearly during the peace process the British were quite willing to see the laws they demanded everybody else uphold, subverted for their own political reasons.

Jonathan Powell has written a valuable political memoir which adds to our understanding of how the British state both overcame the challenges posed to it from republicanism and brought the violent Northern conflict to a close on its own terms. Powell, in spite of his efforts to mask the extent of the republican defeat, nevertheless unveiled the very real shortcomings of the Adams strategy as a republican project.

The lessons we are invited to learn from the Powell memoirs are simple. There was no republican outcome to the republican struggle. At the close of the IRA campaign the British state had conceded no ground. Its conditions for leaving Ireland were the same as they were prior to the IRA campaign: only with the consent of a majority of people in the North. The British also secured the internal solution republicans vowed never to buy into, and through the Good Friday Agreement ensured the intellectual hegemony of the internal conflict model as the explanation for the turbulence that had beset the North for the previous three decades. With the two warring tribes perspective projected onto the world stage the British in true colonial fashion drastically minimised their own responsibility.

The British state’s self-serving case that throughout the conflict it was merely a neutral facilitator, going along with any outcome so long as both ‘tribes’ agreed with it, found more validation than it ever deserved when on the 20th anniversary of the Loughall ambush Martin McGuinness and Ian Paisley competed to tell jokes. If ever the contrast between republican sacrifices made and non-republican goals secured, was captured in one still shot it lay in that moment of laughter; a moment far removed from the laughter of our children predicted by Bobby Sands.

With this in mind, at a conference in England two years ago, I put it sharply to a senior British official long at the heart of British state strategy that ‘you shafted republicans.’ His parry, as simple as my thrust had been sharp, was, ‘no, republicans shafted republicans.’ At that point we could agree not to differ. Whatever the cause, republicans had, without doubt, been shafted.

Great Hatred, there was a lot of it. But at the end there is Little Room for doubt who emerged victorious.

Jonathan Powell, 2008. Great Hatred Little Room. The Bodley Head: London

Book Review in four parts:

1. Great

2. Hatred

3. Little

4. Room

Monday, June 7, 2010

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Little

One thing that politics devotees will find themselves drawn to in the political memoirs of Jonathan Powell is the author addressing some of the more salient issues that came to define the peace process in the public mind. Amongst these was the vexed question of what to do with IRA armaments. The term ‘decommissioning’ for much of the peace process was in a symbiotic relationship with it. Like the term ‘securocrat’ it was omnipresent.

According to Sean Duignan, in his book One Spin on the Merry-Go-Round, Martin McGuinness had sometime around the ceasefire of 1994 told the Irish government ‘we know the guns will have to be banjaxed.’ The task for McGuinness and the leadership coterie he worked within from that point on was to manage the banjaxing of the weaponry while keeping the grassroots bamboozled at the same time. Having their followers chant ‘not an ounce not a round’, while their republican critics looked on incredulous, wondering how the chanters could believe any of what they chanted, was nothing other than a leadership ruse to have sound paralyse vision.

The British, for their own part, were not primarily concerned with decommissioning as the yardstick for measuring ultimate victory over the Provisional IRA. They pushed it more as a means to strategically position the unionists - who were forceful in making the arms question a central issue – at a point where the British needed them to be.

For all Sinn Fein’s huffing and puffing that not a dump would be blown down by the big bad wolf from London, it was in the end a British Army GOC who came up with the suggestion that weapons should initially be retained in a sealed dump. Tim Dalton of the Irish side later informed Powell privately that Sinn Fein had taken up the GOC’s suggestion. Cyril Ramaphosa and his colleague Martti Ahtisaari merely served as the smokescreen which dulled the senses of the Provisional grass roots and allowed the decommissioning process to crank up the gears to a point where full throttle was applied. And still the grassroots, led by the politically challenged IRA middle management, claimed nothing had moved when they alone were left standing at the starting line.

The course of disarmament stretched out endlessly it seemed, as well as being strewn with chicanes along the route. This was acquiesced in by the British due to Blair estimating that breaking the back of republicanism would take place on the strategic theatre of consent rather than in the Scarva battlefield of weapons. Although Danny Morrison once stipulated that decommissioning was the criterion for any IRA surrender the Blair government was more strategically discerning than it was often given credit for.

None too discerning, however, were the unionists whom the British had sought to assuage through pressing home the decommissioning issue, often against their better judgement:

We had expected jubilation at the demise of the IRA and the decommissioning of all its weapons, but instead a strange thing happened. The unionist community fell into a gloom. Tony’s first reaction was to get irritated with them: they had peace, they had the union, the IRA had now gone out of business and yet they still weren’t happy.

During the long, winding, torturous climb to Mount Decommissioning Gerry Adams, in a very revealing comment, said he could not accept one particular set of British proposals at Hillsborough on the eradication of the IRA arsenal. He stressed that his own value, more or less to the British, rested on his ability to deliver, otherwise he would be no different from any other politician. This theme of usefulness to the British state is revisited when Adams told Powell that the Provisional IRA in South Armagh was needed to keep the Real IRA in check in the pubs and clubs of the areas. It was a way of trying to convey to the British state that the Provisionals would not have to go out of existence in order to have a strategic utility for its one time adversary. In essence it was an offer by the Provisional Movement to become an instrument of repression over the republican side in a rerun of the 1920s Treaty debate. Such debates invariably function as demarcation lines which chart out the different roads republicans and their former comrades must travel. The quid pro quo was straightforward enough: Sinn Fein could become a junior partner in the administration of British rule in the North in return for strangling republicanism.

Another news grabbing issue up for discussion in the memoir was the Northern Bank robbery. Powell knew right away that the Provisional IRA was responsible. At initial meetings with him at Clonard neither Adams nor McGuinness tried to persuade the British official of the IRA’s innocence, merely claiming that they had no foreknowledge of it. The assertive refutation of IRA involvement came a month later in the middle of a sustained lie assault on human reason. All party officials seemed to have been instructed ‘more lies for the front’ and duly supplied them. It was February before Adams would make a tacit admission to the British on the robbery. Without directly laying culpability at the door of the organisation of which he was a key member, he said that some people within it had tunnel vision. It was shortly after this and the Robert McCartney killing that Powell noticed Adams beginning to appear shell shocked.

That cumulative effect of both incidents was a defining moment in the peace process. It was like a game of chess where one player makes the wrong move and knows instantly and instinctively that the balance of the board has decisively shifted to the opponent, leaving checkmate as the only outcome. That was the beginning of the end, the moment of realisation by Gerry Adams that the Provisionals had overplayed their hand and that expansionism, the Sinn Fein raison d’etre rather than republicanism, throughout the island would now stutter to a halt.

In penning his memoirs Jonathan Powell seemed to sense that a waffle-weary public was owed some explanation as to why the peace process grinded interminably on for seemingly no other reason than it grinded on. Although the Provisional leadership had a calculated strategic reason for this, wholly unrelated to anything republican, and driven by the expansionist impulse mentioned above, Powell failed to touch on it. Much of the post-GFA foot dragging is explained by him in terms of strategic necessity on the part of the British. London was governed by a perceived need to avoid a split within the Provisional Movement. In 2004 Sinn Fein were still trying to sell the line to the British that there were still many in the IRA hostile to the agreement. But the IRA had long since been defeated by that point.

Gerry Adams at one point argued to Powell that there were serious problems with the middle management of the IRA. Yet, it would be impossible to find a more docile group of people anywhere than the IRA’s middle management. In the early to mid 1980s that stratum’s vital signs were still functioning but could safely be pronounced extinct by the time Powell and Blair had arrived.

The Blair team in dealing with these matters were hardly innovative, making no radical departure from the thinking articulated by Ronnie Flanagan while head of RUC Special Branch. Flanagan cautioned against doing anything that might split the Provisional IRA.

Peter Mandelson alone, seemingly, in the Blair camp, felt it worthwhile bucking against this trend and instead face down Sinn Fein. Historians may eventually conclude that Mandelson had it right and will base such conclusions on the oscillating demeanour of Powell who unpersuasively contends that because of a lack of intelligence on their own side the British had to take the Provisionals’ word for it when they said that it was too difficult to move. Yet Powell admits that he was able to see how Sinn Fein was stringing him along.

That said, there may be a more farsighted reason governing the behaviour of Powell and his colleagues. Lack of intelligence about the internal balance of forces within the Provisional world was hardly the reason for British reticence to push matters to a conclusion. The Provisionals were well enough penetrated. The British were content to play it long and the convenient chimera of a difficult IRA assisted them in the process. We may suspect they were practicing their own counter insurgency strategy and gathering as much experience as possible for future battles that lay ahead with other protagonists. Certainly, by the time of the attacks of 9/11 a view had been formulated in the minds of British strategists that the Islamicist violence made the type of armed action used by the Provisional IRA obsolete. This was articulated by Powell who suggested that the Provisional IRA had by then come to look irrelevant.

If the lack of intelligence was not causing problems for the bedding down of the peace process then the gathering of it certainly was. Here Powell is certain to raise more eyebrows than win nods of approval. Given the time and energy expended by Blair and Powell is it really conceivable that the likely outcome of the IRA spying activity at Stormont was not forwarded to them by Secretary of State John Reid? It seems more plausible that Powell deliberately claimed lack of knowledge on his and Bair’s behalf for the purposes of continuing to mollify Sinn Fein. Why he should in his memoirs continue with what seems an unsustainable position is another matter. At the heel of the hunt Powell and Blair were so certain of IRA involvement in a spying exercise at Stormont that after the PSNI raid on the Sinn Fein offices up on Union Hill they told the party in terms that were anything but uncertain that it had now to make a choice between the armalite and the ballot box.

It was around this point that Trimble began to grow even more forthright in his opinion that the Blair government wanted rid of him. Powell disputes this, arguing that it was John Reid and the NIO who felt Paisley was by now becoming the most likely horse to place their money on.

But Paisley was a steed unlikely to jump his fences until he was assured the horse that Bobby Sands, through his hunger strike, vowed would never be consigned to the Knackers yard was well and truly placed there.

Jonathan Powell, 2008. Great Hatred Little Room. The Bodley Head: London

Book Review in four parts:

1. Great

2. Hatred

3. Little

4. Room

Friday, June 4, 2010

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

Hatred

There are many things that make the Jonathan Powell memoirs valuable as a historical document. Among them is their extraordinary inability to mask, despite the author’s professions to the contrary, the real strategic intent of the British state. When the Blair machine settled into Downing Street in 1997 it locked in perfectly with the backcloth strategically weaved four years earlier by the Tory Prime Minister John Major. The Conservative leader had made it abundantly clear to all and sundry that Britain would not negotiate with anyone on the basis of a British withdrawal from the North of Ireland. When Blair took over the leadership of the British Labour Party he abandoned even the minimalist position of unity by consent.

As soon as Blair and his crew team assumed office he began reassuring unionists that the new administration had no predilection whatsoever toward a united Ireland. If Powell and Blair were feeling their way around the political maze of Northern Irish politics their touchstone was never in doubt: all negotiations with Sinn Fein would without equivocation exclude a united Ireland from the range of outcomes that might be considered.

Despite the misgivings of Paddy Teahon, a leading Irish civil servant, Blair insisted on making the following statement in Balmoral shortly after he moved into 10 Downing Street in which he mapped the strategic parameters.

None of us in the hall today, even the youngest, is likely to see Northern Ireland as anything but a part of the United Kingdom … My agenda is not a united Ireland. Northern Ireland is part of the United Kingdom alongside England, Scotland and Wales … I believe in the United Kingdom. I value the union.

There is not, nor was there ever, any room for ambiguity. From the earliest moment the Blair administration conveyed its strategic intentions. On the Sinn Fein leadership’s first visit to 10 Downing Street Tony Blair explained to Gerry Adams that there was no chance of a united Ireland and according to Powell the British Prime Minister ‘was pleased that Adams seemed to accept that he would have to live with something less than a united Ireland as the outcome of the process.’ How much less was never made clear to the republican grassroots. The Sinn Fein leadership, according to Powell, remained firm in ‘never revealing in full to the movement their eventual destination.’

A key republican demand – the demand which defined republicanism – had been kicked into touch. With or without the patronising ‘old boy’ style of delivery that rubs salt into the wound, the substance was the same. The administration would not even consider providing a discursive veneer as a fig leaf behind which Sinn Fein could conceal its strategic evisceration; the Blair machine rejected outright any suggestion that it become a persuader for Irish unity. It has never once deviated from that position.

Nor can it be claimed that the early Blair position was some New Labour innovation devised by a naive administration that could soon be persuaded to change its mind. There was strategic continuity from the days of Tory rule. From 1993, a year before the first IRA ceasefire, Sinn Fein fully understood that the British through the Downing Street Declaration had, in the words of Powell, stipulated that:

gone was the deadline for British withdrawal; gone was the demand that the British government be a ‘persuader’ for a united Ireland and gone the idea of an act of self determination for all the Irish people.

What outcome other than an internal solution could there then result from any negotiations? By 1998 Sinn Fein was ‘settling for much less in the Agreement than had originally been demanded by republicans in 1993.’

In spite of being fully aware of the boundaries of British state manoeuvrability, and being bereft of any strategic mechanism for dislodging the British from their commanding height, Sinn Fein, from a position of weakness, entered negotiations with the British.

The British approach to these negotiations was clear: they were into the business of wrong-footing and outmanoeuvring the Adams negotiators. ‘Tony again explained the aim was to call Sinn Fein’s bluff.’

All of this helps to shed more light on Sinn Fein’s own claim to have been great negotiators, without equal, if some of the party apparatchiks are to be believed. Even a commentator as experienced as Mark Devenport could recently be found buying into the myth of the party’s ‘negotiating prowess during the peace process’.

From Powell’s perspective:

There was a certain pattern to negotiating with Adam and McGuinness. First they would titillate and suggest things were possible, to get you interested. You would then have to go through a lengthy and tough negotiation on all the detail of what they wanted before, at the eleventh hour, they poured a large bucket of cold water over you to reduce your expectations.

Powell considered this a major weakness and believed that Adams and McGuinness were addicted to negotiations. This worked against the Sinn Fein duo because each time negotiations broke down the party paid a higher price to get them going again.

In terms of negotiating acumen Blair’s chief of staff felt Peter Robinson and Nigel Dodds were much more skilful than Sinn Fein’s team. After a two day bargaining session in November 2006 Powell found it remarkable that he was able to find some crumb that made Sinn Fein happy ‘given all they’d to concede to the DUP in the course of the previous two days.’

It is not necessary to get bogged down in the detail to gauge the extent of the Paisleyite victory over Sinn Fein. The sheer visual impact of Martin McGuinness standing shoulder to shoulder with both the leader of the DUP and the leader of the British police in Ireland to condemn republicans as traitors for doing what McGuinness had long ordered them to do, says more than any in depth political analysis.

For anyone giving to thinking about the matter had McGuinness managed, as he previously promised, to put manners on the PSNI (something a republicanism victorious could have done), he would have Hugh Orde and Peter Robinson join him in condemning draconian police powers backed by repressive legislation. Instead, rampant unionism and a triumphant PSNI had McGuiness stand with them and excoriate republicans. Just do the maths; it takes no great intellectual prowess to figure it out.

Powell hints at a weakness in Sinn Fein’s position being the desperation of Martin McGuinness to get into government with the DUP because of the time and energy he had invested in the back channel to the ultra unionist outfit. While it does not seem plausible to reduce Sinn Fein’s strategic management at a key juncture to the psychological constitution of Martin McGuinness, Powell does invite further reflection on, firstly, how Sinn Fein acquired such a weak hand and, secondly, why the party played it even more poorly than was necessary when they got to the table.

Powell’s overall assessment of Sinn Fein’s negotiating ability was that the party had an eventual goal but lacked any medium term strategy. For this reason they kept running to the British. Sinn Fein, virtually lacking in all ideas, were reduced to rejecting the British ideas. It prompted the comment from Powell that ‘they were far less strategic than they were given credit for.’

The British were content to allow Sinn Fein to crow about its negotiating prowess, having already denied the party the space to negotiate for anything the war had been waged for. A conclusion the reader may be pushed toward is that the British used the Sinn Fein leadership in its own battle to successfully defeat the IRA and then used it again to whittle down all republican demands before the negotiations even began:

It was a remarkable act of leadership by Adams and McGuinness to talk the IRA into peace and to persuade them to settle for something far less than they had demanded in 1993, let alone when the Provisionals were formed in 1969. We were determined to aid them in this.

The greatest negotiators of them all it seems were the British.

Jonathan Powell, 2008. Great Hatred Little Room. The Bodley Head: London

Book Review in four parts:

1. Great

2. Hatred

3. Little

4. Room