Although the republicanism of Gerry Adams and Sinn Fein was by then well into the process of thawing out, circumstances required that a few more short years would elapse before the republican project would drown in the deluge of its own watery waste.

More worrisome for the Good Friday well wishers was that a decade ago, Ian Paisley, leader of the DUP, and grand iceberg of Northern Irish politics appeared and sounded as immutable and impenetrable as ever. Little sign of him thawing out. No matter how titanic the form of any political initiative it seemed destined to splinter apart on that bellowing rock of bigotry.

Yet today not only has the rock crumbled but the old pirate who for long reigned over turbulent Irish political seas is about to make the career trip to Davy Jones’s locker. In March Paisley announced his dual retirement as leader of British Northern Ireland and leader of the DUP.

Despite the claims, true no doubt, that he was forced to walk the plank he did not take the plunge until scoring an outstanding achievement. That was to lock republicans ever more securely into a political structure they had waged a long war to destroy. The Northern Ireland state, which the Provisional IRA leadership stormed in wave after wave of ultimately futile attacks, hurling the lives of their own selfless volunteers at it, is now hermetically sealed from political unity with the rest of the country by the consent principle.

With the two extremes of Northern Irish politics, as they have long been dubbed, now cooperating in the North’s micro government, there has been some anguished wailing at the ostensible rewarding of the extremes accompanied by a lament for the collapse of the centre ground. Such a sketch is far removed from the actuality. Those drawing it use sable hair from the last century to paint the world of today.

The extremes have not been rewarded for extremism but for having abandoned it. The victor has been the centre ground. From a unionist perspective the current arrangement is Trimbleism minus Trimble. Some of the internal furniture has been rearranged since the agreement of April 1998, but the external structure is essentially what David Trimble crafted.

What Paisley achieved, only by standing on the shoulders of Trimble, was to up the entrance fee for Sinn Fein’s admission to the northern executive. In doing so he chose not, as promised, to force it to wear sackcloth and ashes. He preferred that Sinn Fein parade naked, stripped of every publicly identifiable republican asset, to the echo of his own bellowing boast that he had smashed the republicanism of the party. The outcome: he pulled the former republican body even further into the political centre, forcing it to drop most of what had earned it the tag ‘extremist’ in the first place.

The centre ground has not imploded. Rather it is now the largest political space in Northern Irish politics with virtually all elected representatives standing on it. It is not driven by the politics of the extreme but dwarfs like never before those on the extremes. In fact there are signs that those considered the great extremists are now to become casualties of the momentum that carried them to the centre.

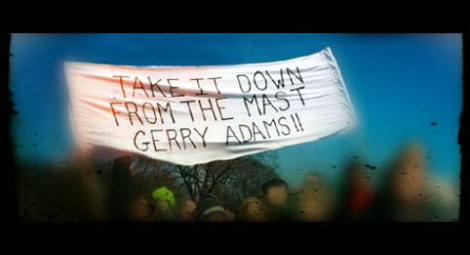

Ian Paisley has had his short sojourn in the sun and is currently beginning his departure to the shade. Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams now stands increasingly isolated as the sole remaining dinosaur of Northern Irish politics. There are no longer kindred spirits into whose midst he can blend where the longevity of his leadership can take cover. Other public figures have been around just as long but not as leaders of political parties. The leaders of all other Northern political parties have been appointed this millennium. Adams now looks like an antediluvian figure from the 1980s. For a quarter of a century he has ruled his party unassailed. Because democracy in a totalitarian party is a façade rather than a means to initiate change, when change does come it is rarely the result of a long process of open democratic activity. The coup de grace is usually administered courtesy of a cabal conspiring against Caesar. How much did we really see of the internal DUP battle to give Paisley the shove?

In recent days prominent Adams backers – loyalists in the Irish context being an inappropriate choice of term – have been noticeable in seeking to distance themselves from any notion that he should continue holding the whip hand until death us do part. In the Andersonstown News - a local paper in Adams’ West Belfast constituency with an unchallenged history of being staffed by Adams devotees - the paper’s editor, writing under his well known pseudonym , was scathing of Adams’ record as a Westminster MP. The editor also protested the length of time Adams had been around.

20 years. Two decades. Four parliamentary terms. Four US Presidents. Two Popes. 11 Secretaries of State. Five UN Secretary-Generals. Five Taoisigh. Five Prime Ministers.

Following on the heels of this Niall O’Dowd, editor of the Irish Voice in New York, and a long time echo chamber for the thoughts of Gerry Adams, was telling students on a visit to Belfast that the Sinn Fein president had been an outstanding leader but was weighed down by too much baggage from the past to be able to take the political process to the next stage.

Interesting stuff but no guarantee that Gerry Adams will accompany Ian Paisley as he returns from the fair. But it is the most significant indication to date that the groundswell of opinion ready to question Adams, if not actually challenge his leadership, can no longer be exorcised from public discourse and banished to dark places where it can be safely strangled by the Sinn Fein thought police.

If Adams and Paisley, things of the night from Northern Ireland’s darkness, can slink off arm in arm there are many who will see in it the rise of a new dawn.

First published Parliamentary Brief, April 2008