It quickly became Kafkaesque. At the first hearing the public, press, myself and my lawyers were cleared from the court so that the PSNI could present their arguments in camera. How could we mount a defence when we didn’t even know what police were saying? We were fighting a case from a massively disadvantaged position – Suzanne Breen

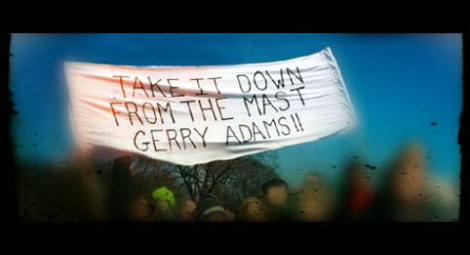

The recent judicial attempt to clip the wings of Ian Paisley Jnr is to be seen in the context of an instinctual urge by the state to erode the ground underpinning the logic of protecting sources which allow vital information to enter the public arena. It should simultaneously remind people of the importance of the victory achieved by Suzanne Breen in a Belfast court and warn them of the temptation to rest on the laurels of the Breen achievement. Although it was the first time since the Terrorism Act of 2000 that the protection of sources has been judicially approved and enshrined, nothing should be taken for granted. When Suzanne Breen wrote after the verdict in her own case, declaring it a triumph for press freedom across Europe, it can hardly be said she was exaggerating. However, while she forced the PSNI to pull its horns in and desist from goring a vital principle of journalism, the state has clearly not thrown in the towel, referring instead to use it as a gag to suffocate Ian Paisley Jnr.

Suzanne Breen was up against it from the get go. As she reported ‘the police were said to be absolutely confident they’d win.’ They had good reason to. The precedent favouring journalists on the issue of protecting sources was set almost a decade earlier in the case of Ed Moloney who, like Breen, was also Northern editor of the Sunday Tribune. The state felt less assured and steady on its feet then. It was walking on eggshells and was vulnerable to exposure. A murder its own people had been involved in through collusion with loyalist militias had not been solved and the one person facing prison in relation to it was the journalist who had brought to light many of the unsavoury aspects of the case. At the time there still existed a serious swathe of opinion willing to challenge the British policing regime.

Breen by contrast was protecting a source in the deeply unpopular Real IRA, and in the eyes of many people would be unable to elicit little in the way of popular support for her stand. As in the days when the Provisional IRA was at war with the British state there remains a deep hostility within the ranks of officialdom toward any voices from within armed bodies opposed to the state. The Real IRA unlike the Provisionals is a body with little support in the nationalist community and the PSNI must have felt they were pushing a door being opened in advance of their arrival by those previously most critical of the force.

In some areas the PSNI had been involved in more serious violations of human rights than had been when operating under its old RUC name; the detention of people in custody for up to 28 days a case in point. Yet there was little in the way of opposition from the political parties to the force’s behaviour. It hardly expected a serious challenge to its latest encroachment and could even claim to have been given the green light for the move by the comments of the Deputy First Minister who lambasted ‘dissident journalists.’

However propitious the conditions as viewed by the police their reading was one neither shared nor acquiesced in by Breen’s colleagues in the journalistic profession, nor by those in the wider anti censorship community. Despite the green light they were determined to hold up a very large ‘stop’ sign; so large that it was visible to more people than the PSNI imagined existed.

A vigorous campaign in defence of the targeted journalist was launched. It cut right across the political divide, drawing the support of many people, some of whom are more used to signing bits of paper against each other rather than signing the same bit in unity against the PSNI accumulation of powers. Commenting on the sense of purpose within the journalistic community and the strength of its opposition to the PSNI assault on media freedom the beleaguered Sunday Tribune journalist explained: ‘for the first time in a source protection case, a range of eminent journalists would be called to give evidence and defend our profession’s principles and practices.’ More than 5000 signatures were gathered for a ‘We’re Backing Suzanne’ petition which was carried in the paper of which she is Northern editor.

From a human rights perspective the ruling against the PSNI by Judge Tom Burgess was heartening in that it underpinned the claim by Breen that the police should not be allowed to display a wanton disregard for the lives of its citizens by putting them at risk from armed militias. When the moment the case was initiated it was felt by many that if Breen were to win it would be on these grounds. However, Judge Burgess went much further and acknowledged the journalistic issues at the heart of the case. The court not only ruled in favour of Breen’s human rights but also in favour of her as a journalist who unflinchingly insisted on the profession’s need to protect sources if a function as vital to society as policing itself was not to be rendered dysfunctional.

John Ware a prominent journalist with Panorama said ‘there is meant to be progressive policing in Northern Ireland. If this is progressive policing I’d hate to see what regressive policing would be like.’ The state of political affairs in the North today is such that citizens there must rely on the journalistic profession and anti-censorship community to push back the encroaching boundaries of regressive policing and not the politicians.