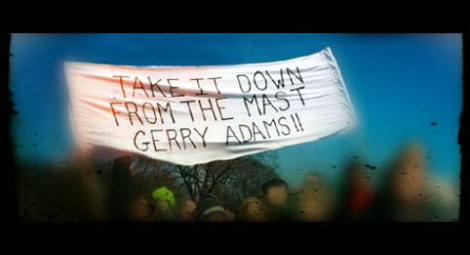

With that we are denied the comfort zone of flaying the Brits or loyalists for bearing the unwanted distinction of having inflicted mass murder on an unsuspecting civilian population. We are also reminded of Gerry Adams’ lucid 2001 view that terrorism is ethically indefensible because it wilfully targets civilians. While the events at Enniskillen do not disprove Adams’ assertion that the IRA was something other than a terrorist organisation, they point firmly to one conclusion: there were some within the IRA who did not share Adams’ view of terrorism as unethical.

The reconstruction of the attack also ruptures another comfort zone; that there is a moral chasm which separates the Omagh and Enniskillen bombs. The immediate difference is one of dates. In fact, it may well be argued that the Omagh bombers killed the innocent through incompetence whereas the Enniskillen bombers killed them through design which makes the 1987 bombing more reprehensible than the 1998 one. Terms such as ‘massacre’ when used to describe Omagh depreciate in value if not applied to Enniskillen.

Prior to the documentary going out there were suggestions that Martin McGuinness would have the finger pointed at him as the person responsible for giving the go ahead for an operation certain to kill innocent people. In the event the programme was not as strong on this point as had been suggested. However, McGuinness badly erred in crying ‘securocrat’ before the programme was aired. In the semaphore of the peace process securocrat invariably reads as ‘guilty.’ It hobbled any credible defence he might have made. The evidence presented against him by Peter Taylor was arguably less damaging than the plea of ‘securocrat.’

Moreover, his dismissal of the case against him was not reinforced by his assertion that he did not serve on the Northern Command at the time of the bombing. The matter has been fairly well documented in a myriad of credible publications. The late Brendan Hughes, for example, in interviews given to the Spanish academic Rogelio Alonso firmly places McGuinness at the heart of operational decision making in the period after Hughes was released from prison. Hughes left Long Kesh a mere year before the Enniskillen bombing. Consequently, McGuinness’s role at senior levels within the IRA now seems a commonplace belief. If he says in the same breath that he had no foreknowledge of the bomb nor was he on the IRA’s Northern Command at the time it was carried out he actually invites people to treat both assertions with equal scepticism.

Article continues

More incongruity for Sinn Fein came when those the party so readily endorses as the only legitimate forces of law and order north and south lent their weight to allegations that some of its key leaders had foreknowledge of an operation that would certainly result in civilian fatalities. If political policing was ended by Sinn Fein’s decision to support the PSNI why is Martin McGuinness accusing a figure as senior as Norman Baxter of blatantly engaging in overt political policing?

As he did in an earlier documentary on the Brighton bomb Danny Morrison argued the case for the defence but without the passion of old. It is not enough to kick for touch in exchanges where the opposition is scoring points. While Morrison scored no own goals his pedestrian performance signalled, ‘Houston we have a problem.’

And the problem was not alloyed even by the PSNI commentator demonstrating a deranged perspective with his claim that another operation aborted on Poppy Day was aimed at children in the Boys and Girls Brigade who were legitimate targets in the eyes of the IRA. Such eagerness to believe the worst displayed a prejudiced rather than an analytical mind. Yet such prejudice breezed through effectively unchallenged in this documentary.

1987 had been a trying year for the IRA. It had sustained the heaviest casualties of its campaign with the SAS ambush at Loughall which led to 8 IRA funerals in a week. This occurred against a ‘battle of the funerals’ backdrop in which the RUC attacked mourners and disrupted corteges, on one occasion delaying the burial of a North Belfast IRA volunteer for days. With this in the background it is possible that someone may have decided that like must be met with like, a message transmitted to the RUC that the measure you give is the measure you get. Certainly some Belfast volunteers at the time admit to having felt that this was a response to the funeral attacks. But, perhaps of more significance, they were quickly disabused of the notion by senior figures; an indication that that grassroots volunteers were not as restrained as their leaders.

Furthermore, while there is a viewpoint circulating that operations such as the Enniskillen bombing were allowed to happen by some IRA leaders as a means to making the armed struggle appear indefensible, thus giving legs to the peace process as an alternative, much more evidence would be needed before this perspective takes hold. The then republican leadership’s response to the killing of Harry Keyes not long after the Poppy Day massacre by a Fermanagh unit of the IRA suggests that such operations were an embarrassment to the peace process lobby rather than an aid. A number of years earlier the leadership had ruled out bombing the Droppin’ Well Inn, later targeted by the INLA. The reasoning was simple: in order to kill large numbers of British troops an unacceptable risk would be posed to civilians.

In 1976 the notion that the IRA would deliberately massacre a civilian population was not all that challenging to the Provisional common sense of the day. Whitecross is a case in point. 11 years later however, it would fly in the face of where the leadership then stood. While those who planted the bomb knew exactly what would be the outcome, for now botched and bungling seem more appropriate terms than deliberate when applied to the leadership’s role in the Enniskillen bomb. The leadership would almost certainly have approved a coordinated series of operations on the day. It seems unlikely that it gave the go ahead to kill civilians in those operations.

This documentary has raised difficult questions for Sinn Fein leaders. In a sense it carries the imprimatur of a yellow card for the Deputy First Minister. With Ian Paisley having being shown the red one it must be dawning on Martin McGuinness that if the past is to be truly put behind then more people are concluding that so too must its relics.