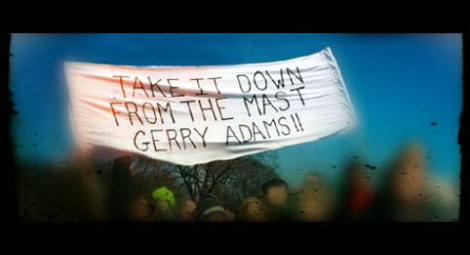

The 3 senior escapees interviewed for Breakout, Gerry Kelly, Brendan McFarlane and Bobby Storey were knowledgeable and articulate. Their actions on the day 25 years ago were characterised by nerve and courage. The escape came at a point in time where it could genuinely be said that the IRA was courageous and imaginative, words that have since come to be corrupted and devalued into meaningless vacuity by the peace process.

At the time an IRA that could pull off such a feat seemed capable of taking its war to levels where the British state might find its Irish strategy flummoxed, leaving it little choice but to begin a process of disengagement. The catastrophic failure that eventually befell the IRA courtesy of the peace process was not considered a remote likelihood in 1983. Were the food lorry that weaved its way to the prison tally lodge to have displayed, stencilled on its side, the words ‘Paisley will be our leader – criminalise the physical force tradition’ would prison staff seriously have risked their lives to prevent it?

The escape was meticulously planned, its impact instant and lasting. Each of us left behind in the prison on the day will remember exactly where we were and what we were doing at the moment the news came through that our comrades in H7 had achieved the impossible. It seemed amazing that it could have been pulled off. But those who thought big had done it.

The thought and precision that went into both the planning and execution of the operation that took 38 prisoners on a voyage of non-discovery right to the perimeter wall diminishes not at all when it is considered that on the day a major enabling factor was the incompetence of the screws. Many prison staff showed unquestionable bravery but a combination of systemic failure underpinned by bungling lackadaisical individuals was an indispensable ingredient in the escape without which it would most certainly have failed. Clear vindication of the maxim that the best laid of battle plans do not survive contact with the enemy. One viewer described it to me on the day after Breakout aired as having the appearance of one big fiasco. This I would argue was more down to the screws than the prisoners.

By the time it had unfolded its way to the tally lodge the great plan had unravelled. Those at the scene say that only for the on-the-feet thinking and intervention of Bobby Storey the 19 who eventually made it to freedom would have joined their battered, bruised and bleeding comrades in the cell blocks after being forced to run a gauntlet of baton wielding screws and snapping Alsatian dogs.

Storey for his part became a hate figure for prison staff. Seen as having rubbed their noses in it and safely back in their grasp, it was not long before reports started to filter onto the wings from the screws’ mess that inebriated staff were discussing poisoning his food.

Of the three who appeared on Breakout, Kelly was the most interesting. Loquacious and witty, he anecdotally laced his narrative with humorous vignettes which showed that much more goes into human situations than a detached plan hatched only from the sombre and the serious. Many years ago when I had written a review of an earlier documentary I had commented to the effect that Kelly had been strategic in his management and coordination of the getaway. He later said to me that he had been strategically trying to bolt as fast and as far away from the place as possible. This self effacing style of humour easily led to Gerry Kelly being the star of the show in terms of the documentary. From him the blend of the military machine and human personality was probably the most balanced part of proceedings.

Bobby Storey for his part sought to infuse his presentation with martial aura. It failed to fly. While his military prowess is undoubted the performance paled judged against Kelly’s. Use of state terms like ‘under arrest’ in a manufactured monotone tends to run against the grain of the anti-state ethos practiced by radical insurrectionists. The end result is an awkward exposure of the joints. A number of years ago in Edinburgh I was at a dinner table next to a SAS officer who was central to coordinating the 1980 siege bust at the Iranian embassy in London. We spoke for most of the evening and it was clear that military authority fitted him like a glove. Even, clipped, precise, authoritative intonations flowed from his lips as we discussed his regiment’s battle against the IRA. That type of cadence is perhaps best used in conventional armies staffed by Clive Fairweather. Applied to a guerrilla force led by Bobby Storey it carries more like emulation and merely reminds listeners and viewers that imitation is the greatest form of flattery. In the first case it sounds natural in the second, ersatz.

Storey was more authentic in describing his euphoria at the escape having succeeded despite the fact that he had been recaptured yards from the prison. There was a selflessness to it that is easy to reconcile with his character.

While the IRA ultimately lost the war, Breakout demonstrated only too well the commitment, military ability, intelligence and limitless patience of its volunteers. History will come to judge them as having been poorly rewarded by the project they invested so much in trying to sustain.